[Of course there will be spoilers!]

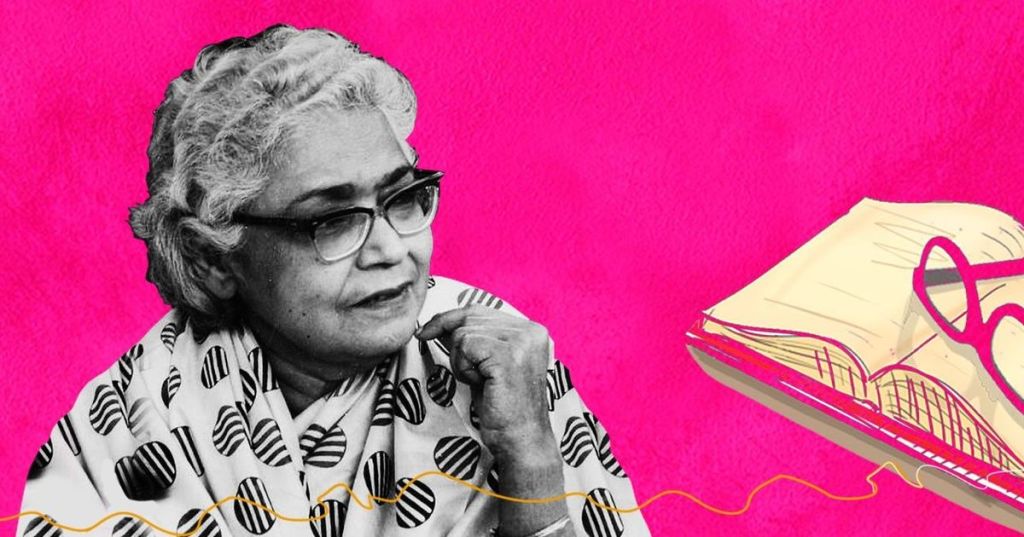

Against all odds, Ismat Chugtai carved out a niche for herself. She was born into an orthodox Muslim family in Badayun, in the midst of 1915, and above all, female. With the pen as her sword, she battled against prevailing societal norms regarding “proper” female conduct and roles. She was amongst the esteemed Urdu writers of her time including Saadat Hasan Manto, Krishan Chander, and Rajinder Singh Bedi. Chugtai’s tales of everyday life are rife with themes of female sexuality, bourgeois gentility, marriage, subjugation of the women and are deeply introspective and feminist in tone.

The short story “All For A Husband” is serious in subject matter but comical in form. In this tale, a young college-educated woman travels alone from Jodhpur to Bombay for an interview. Her fellow female travellers bombard her with queries about her personal life (Is she travelling to her maika or sasural?) and are unable to believe that the narrator isn’t married. The narrator desperately wants to rise against the prevailing hive mind but she gives up and tailors a faux husband: a coolie, with whom she has eight children!

Chugtai masterfully crafts this story of an independent woman who is fed up by the idea that she should always belong to somebody and that her worth is defined by her husband. Her fellow travellers are obsessed with husbands especially those that are not their own.

“Of Fists and Rubs” is a rather unpleasant story about many things but in particular two socially downtrodden women called Ratti Bai and Ganga Bai. The author, the supposed narrator, paints a powerful rich/poor, urban/rural dynamic. In order to send money back home women from villages work in factories, sell vegetables illegally on the street without licences and the very desperate resort to begging or prostitution.

Ratti Bai and Ganga Bai spend their days in the suburbs of Bombay and are uprooted from their traditional spaces of work. The author recounts in a flashback that she met them in the hospital while admitted for her daughters birth. The women constantly vilify each other and in one particular instance quarrel over discarded cotton pads. This scene speaks of the inhumanity and hardships for such women who are uneducated and tortured by socio-economic conditions. The story culminates in the author learning the various horrific methods of abortion used by these poor women: “Oh, god, such a dreadful punishment for bringing life into this world.”

The author faces the dilemma of being reticent on what she has learned or to break the bondage of orthodox traditions and speak her mind. She chose the latter. Her writing is stripped of romanticism and its casual realism shocks the reader.

In a different vein, the first chapter of “A Strange Man” is about the Bollywood film industry. Dharm Dev, a successful actor, director and producer falls into an all-consuming love affair with Zarina much to the betrayal of his wife Mangala. Ismat Chugtai’s writing is cynical, sardonic and her career as a scriptwriter gave her an insight into the world of film and the tribulations of stardom, fame and love.

It is safe to say that Chugtai’s most famous piece of work is “Lihaf” (1942), a tale of alternate sexuality. Ever since its publication in the journal Adab-i-Latif, it generated controversy and she was levelled with charges of obscenity in 1944. In the story, a young female protagonist recounts the tale of her stay with her aunt Begum Jaan. Reading between the lines, the story is anything but innocent. The Nawab is more interested in spending his time with young boys and ignores his wife who seems to wither day by day.

The Nawab treats his her akin to the furniture in his house. Chugtai attacks patriarchal norms and unveils Indian social taboos. Begum Jaan, repressed and sexually frustrated, enters into a lesbian relationship with her maid Rabbu. Since she could not derive pleasure from her husband she looked elsewhere. “Lihaf”is an important story because it throws light on the female psyche and female sexual desires that patriarchy ties to hide, ignore and cover.

Female self-representation and realism are the two cornerstones of Ismat Chugtai’s writing. A truly progressive soul, she wrote about “women’s lives particularly their cultural status and their myriad roles in Indian society.” Tahira Naqvi labeled her as a “rebel,” and that she was a “woman who never forgot who she was, who was glad to be a woman, who, if offered the choice, would be a woman again and again.”

Manto once wrote:

“I told Ismat,

I liked your story “Lihaf.” Your special merit lies in using your words with utmost economy. But I’m surprised that you’ve added the rather pointless line, “Even if someone gives me a lakh of rupees I won’t tell anyone what I saw when the quilt was lifted by an inch.”

“What’s wrong with that sentence?” Ismat had retorted.

I was going to say something but then I looked at her face. There I saw the kind of embarrassment that overwhelms common, homely girls when they hear something unspeakable. I felt greatly disappointed because I wanted to have a detailed discussion with her about every aspect of “Lihaf.” As she left I told myself, “The wretch turned out to be a mere woman after all!”

Ismat Chugtai’s stories are grim and realistic views on the subject of women. These themes are rhetorical and subtly repeated not only though the voices of the protagonist but also the author herself. These voices are profound, the stories are distressing and eye opening but most of all, relatable.

You must be logged in to post a comment.